- Home

- David Brin

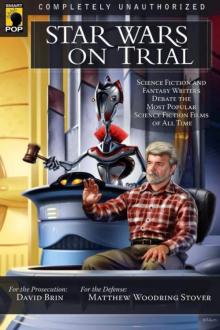

Star Wars on Trial Page 12

Star Wars on Trial Read online

Page 12

There is nothing in the Jedi Code, or the religion, morals or ethics of Star Wars, that make any sense of Obi-Wan's action of turning his back on a severely wounded Bad Guy and walking off to go tell Nayland Smith that Fu Manchu must have died in that explosion. No one could live through that!

But Obi-Wan walks away because the script requires it.

And that's all there is to the Force in Star Wars, both in this scene and all the others. The Force is not about religion or ethics or anything. The Force is what the script forces.

John C. Wright is a retired attorney, newspaperman and newspaper editor, who was only once on the lam and forced to hide from the police, who did not admire his newspaper. In 1984 he graduated from St. John's College in Annapolis, home of the "Great Books" program. In 1987 he graduated from the College and William and Mary's Law School (going from the third oldest to the second oldest school in continuous use in the United States), and was admitted to the practice of law in three jurisdictions (New York, May 1989; Maryland, December 1990; DC, January 1994). His law practice was unsuccessful enough to drive him into bankruptcy soon thereafter. His stint as a newspaperman for the St. Mary's Today was more rewarding spiritually, but, alas, also a failure financially He presently works (successfully) as a writer in Virginia, where he lives in fairy-tale-like happiness with his wife, the authoress L. Jagi Lamplighter, and their three children: Orville, Wilbur and Just Wright.

THE COURTROOM

DROID JUDGE: Mr. Stover, do you wish to cross-examine?

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: Absolutely. Mr. Wright, first I suppose I'd have to ask about your definition of a "real religion," which I quote here: "A real religion addresses metaphysics, spiritual powers, martyrdom, ethics, fate, salvation, miracles and life after death." Are you aware that by a strict application of this definition, you've disqualified the bulk of our world's spiritual traditions? Was this Christian/Islamist bias intentional?

JOHN C. WRIGHT: Objection; leading the witness. Mr. Stover is trying to palm off an assumption on the jury by making a logically impermissible statement in the form of a question.

DROID JUDGE: (apologetically) Mr. Wright, you cannot object. You are a witness, not counsel.

JOHN C. WRIGHT: I'm not asking that the counsel's question be ruled out of order; I'm merely pointing out a logical flaw in the question. Mr. Stover states that non-Christian religions on Earth do not have metaphysics or views about life after death, or the other qualities listed here. If he means that a non-Christian religion can be found that lacks one the qualities listed, the statement is correct but irrelevant; if he means that all non-Christian religions lack any of the qualities listed, the statement is false.

Certain religions on Earth are more complex or simple, depending on their history. All real religions have at least some of these properties I list: I do not make the statement that all religions have all of them. Some do not revere martyrs, for example, and others do not attribute spiritual powers to their practitioners. For the purpose of my argument, I need but show that the Force in Star Wars does not address any of the items on the list, to show that it is not a religion.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, do not be deceived by a crass rhetorical trick of calling my position a "bias." Obviously the honorable counsel for the Defense has nothing else to present to you by way of argument.

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: So the short answer is, "I meant `or' instead of `and' (maybe 'and/or')," and no bias was intended. Fine. You could have just said so.

Moving on.

Would your reaction to the "religious" aspect of Star Wars change if the goal of the "religion" involved was not reward in a life after death, but rather a virtuous life in this existence, as in Judaism? Would your reaction change if the issue were not Salvation, but rather Enlightenment, as in Buddhism? If, in fact, the most profound realization of the spirituality involved was the tat tvam asi-thou art that, the great spiritual principle of non-duality, the fundamental unity of All That is (that "binds the Galaxy together") -which is the goal of religious and spiritual practice from China and Japan through India and the Middle East to nearly all Western mystic traditions?

JOHN C. WRIGHT: The question again contains a logically impermissible inference. Mr. Stover is trying to attribute to an argument a conclusion not in the argument, a rhetorical trick called a "straw man argument"; instead of addressing the questions raised, Mr. Stover rails against an imaginary opponent constructed to be weaker than his real opponent.

If I had made this following argument: "All real religions are about winning afterworldly rewards, and Star Wars lacks this and ergo is not a real religion" then his comment would counter that argument. But that is not the argument I made; ergo his comment is irrelevant.

There is some palaver in the movies about avoiding anger, but no hint that the goal of the Jedi is to become "one" with the Force after death, or to abide by the laws honoring the covenant God made with his ancestors, or to escape from the woes of reincarnation into detachment of Nirvana.

Nowhere in my article do I mention one "goal" for religion as opposed to another. I merely point out that the "goal" of studying the Force is to do way-cool ninja-leaps.

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: For the record, the goal of studying the Force is to become a Jedi, which by definition involves oneness with the Force (not in the afterlife), and adherence to a strict code of conduct developed over 25,000 years.

Moving on.

Are you familiar with the Buddhist doctrine of the Eightfold Path, where all daily activities, pursued in the proper spirit, lead toward Enlightenment? Are you familiar with classical Zen, which finds Enlightenment specifically the study of the martial artstraining to do the earthly equivalents of, as you so vividly put it, "super-ninja-leaps with Way Cool psychokinetic powers." If study of the martial arts can be a religious practice on Earth, why not in Star Wars?

JOHN C. WRIGHT: I am quite familiar with authentic Zen Buddhist practice. I once studied at a Zendo under a Roshi.

The question yet again contains a logically impermissible inference. This is the formal logical error of the excluded middle. Merely because some Buddhists can use martial arts as a meditative technique appurtenant to their religion, it does not follow that all martial arts studies constitute a religion.

Certainly the Jedi in Star Wars are meant to have an exotic, oriental flavor to them: they are fencing with nuclear kendo sticks, after all. But the same flavor could be attributed to any movie where ninjas fly around on wires or perform spooky magic tricks. The spooky ninja-magicians in Star Wars are following in the footsteps of Bruce Lee, not following the footsteps of the Enlightened One.

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: I now direct your attention to your observation "If the Force were a god like Odin or Zeus, the audience would be puzzled why the Sky Father is supporting both sides of the conflict. Therefore, the Force itself has to be neutral, an inactive and nondemanding sort of god, etc." Since you are apparently the last person on Earth who hasn't heard that the Force was a direct metaphor for the ancient concept of the Tao, let me direct your attention to Stephen Mitchell's translation of this passage from the Tao Te Ching: "The Tao does not take sides."

Perhaps it would be easier for you to understand if, instead of the Force-instead of calling it a god, which it is not, and is never said to be-we call it Life. After all, Life is what it's about, yes? And Life gives us everything that's good, and a great deal that's bad: Poetry and art, beauty and family, civilization and science ... and it also gives us smallpox and Ebola, aggression and greed and jealousy and murder. Without bias or prejudice. Without taking sides. Whether it's good or evil depends on what we do with it. Does using the word Life as the metaphor help clear up your confusion?

JOHN C. WRIGHT: The question yet again contains a logically impermissible inference. It is an informal error of logic to assert that "everyone knows" such-and-such, or to address the person rather than the argument. The former is called argumentum ad populum; the latter is called ad

hominem.

The formal logical error of the undistributed middle is also present. Merely because a misunderstanding of Taoism represents the Tao as ethically neutral does not mean that all ethically neutral phenomena are religious.

Electromagnetic energy, for example, can be used both for the electric toothbrush and the electric chair. It is neutral. By the logic of the honorable counsel for the Defense, a film portraying electricity as neutral would be "religious" because life is neutral.

A vague awe and respect for "the life force" is not a religion. It is not even a philosophy: it is a sentiment. Star Wars does have a sentiment. It does not have a religion.

If "everyone" knows that Star Wars is a metaphor for Taoism, then "everyone" has not read enough Lao Tzu to have a serious discussion on the matter. I suppose that is fine, because those who follow the Tao say that the Tao that can be spoken is not the spoken Tao. Those who truly follow, on the other hand, follow, and do not say.

The Tao might not take sides, but, under heaven, there is a way to follow the Tao and a way not to follow it. Taoism has a definite ethical character and metaphysics which Star Wars does not have, and, as a bit of boy's adventure fiction, is not meant to have.

The question is not whether the Force is neutral, but why it is neutral. It is neutral because the plot requires duels between good and bad psychic swordsmen.

It is not neutral because the movie is Taoist in message or sentiment.

It is Taoist to say: The wise ruler sees that the bellies are full and the minds are empty. The crooked tree is useless to the carpenter, and therefore it flourishes. What is the shape of an uncarved block? What did your face look like before you were born?

It is not Taoist to say, "Do not give in to fear and anger, or forever will it dominate your destiny!" or, "In my experience, there is no such thing as coincidence."

I do not recall, in the scene where Qui-Gon measures the midichlorian blood count in his young apprentice, that what was being measured was Anakin's potential to embrace these questions and paradoxes.

If Star Wars counts as a movie of religion equal in stature to Taoism, why, then, so does Flying Ninja Guillotines of Death or Lightning Swords of the Shogun Executioner.

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: I have no further questions for this witness. Pointing up the numberless confusions and misrepresentations in the balance of his testimony serves no purpose, as many of them proceed from his fundamental misunderstanding of the metaphysical premises of the Saga; I'm simply trying to help him understand, not to embarrass him.

DAVID BRIN: Objection!

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: You object to my trying to help him understand?

DROID JUDGE: Sustained. Save your speeches for your closing statement, Mr. Stover.

MATTHEW WOODRING STOVER: Fine. The Defense's witness can handle the ethical end of the argument; I call novelist, critic and allaround swell guy Scott Lynch.

TO LIE during my interview with the evaluation board of my first volunteer fire department. Because of Star Wars.

Or perhaps it was more of a calculated omission. In response to the question, "Why do you want to be a volunteer firefighter?" I rattled off a string of boilerplate platitudes-it seemed like it might be fun and interesting, a chance to serve the community, nobody likes to see his neighbors screaming and on fire, et cetera. The members of the board nodded sagely, examined the line on their evaluation form that read Possible Raving Freak YIN, circled N, and that was that.

How might they have replied if I'd cleared my throat and said, "I've wrestled with a deep-seated desire to be ajedi Knight ever since I was old enough to tie my own shoes, and this seems my best chance to act on that desire in some fashion"? Replied? Hell, they would have pinned me the floor and helped the nice men in white coats jab the needle into my arm.

Nonetheless, it's true. I have a Jedi complex dating back to that fateful afternoon in 1983 when my father took the five-year-old ver sion of myself to see Return of the Jedi, a film that was to my brain what an industrial electromagnet is to a handful of iron filings. Some days, I might as well be standing on a street corner holding a handlettered cardboard sign: Will deflect blaster bolts with lightsaber for food.

It could be said that the Jedi represent an ideal I have never been able to forget-an ideal that, in my own bent and silly and imperfect fashion, I still try to cherish.

Dr. Brin, in his generous introduction (and I do mean that-remember, this is a guy who's carried out nothing less than an intellectual serial mugging on the prequel films over the past half-decade), alludes to the emotional impact of The Empire Strikes Back and the promise therein, in his words, "that meaning can coexist with adventure."

The Star Wars films, like the first Matrix film (my much-abused brain recoils from acknowledging the existence of the later two), possess what I often refer to as "opt-in philosophical depth." They can be enjoyed, without diminishment, as nothing more than amiable, fast-moving action/adventure pieces overflowing with visual innovation. They can also be divertingly dissected on a deeper level-the level of Campbellian journeys, mythic resonance, political allusion and ethical argument.

It is this last quality, the ethical component of the Star Wars films, that I credit in hindsight with cementing them as the cultural cornerstone of my early years. My childhood was filled with flashy media-transforming robots, laser blasts, gun battles, spaceships and so forth-but only the Star Wars films seemed to provide instruction in something to aspire to. I was raised atheist in a home pleasantly free from political, philosophical or theological dogma, and I am unashamed to admit that most of my initial notions of higher virtue were shaped by the actions of fictional rebels-and one fictional knight-in a galaxy far, far away.

LET'S TALK ABOUT WHAT WE'RE NOT GONNA TALK ABOUT

Now, technically, the subject of religion in the Star Wars films comes under my purview along with ethics, but I'm not going to pound many keys on its behalf. I consider the topic too slight to discuss with more than grunts and hand gestures, unless those involved in the discussion want to spin wild exaggerations and extrapolations of the subject to keep the conversation going. Frankly, I'd rather stick a dry spaghetti noodle in my ear and attempt to scratch my hypothalamus.

Simply put, the "religion/spirituality" (quotation marks well deserved) of the Star Wars films, as revealed on-screen, amounts to nothing worth qualitative analysis. The closest any character comes to uttering a religious opinion is Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back:

YODA: Size matters not. Look at me. Judge me by my size, do you? Hmm? Hmm. And well you should not. For my ally is the Force, and a powerful ally it is. Life creates it ... makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter.

However, inasmuch as this has the outward appearance of religiosity, it must be remembered that Yoda has nine centuries of insight into the nature of life, death and the Force-coming from him, this is not an expression of theological opinion but rather a straightforward report on how the universe functions. It's the metaphysical equivalent of a mechanic explaining how your car's alternator works.

There are several references in A New Hope to the "religion" of Darth Vader and Obi-Wan Kenobi, but I think we can safely dismiss those as a mere expression of the context in which laymen (Han Solo, the Death Star command staff) frame the mysterious abilities of the Force-sensitive.

Although the Jedi of the prequel trilogy are steeped in the trappings of religion (they have a "temple," they meditate, they have a considerable fetish for robes and platitudes), it seems clear that they do not pray and they do not anthropomorphize the Force. The attitude the Jedi display toward it is akin to that of a nuclear technician to his reactor-respect and veneration, certainly, but not worship. Additionally, their meditation seems mostly to be a form of mental self-maintenance, designed to prevent them from exploding into kill-crazy lightsaber rampages for minor aggravations like, say, Meatless Tuesdays in the Jedi Temple cafeteria.

Other th

an that, no character in any of the films expresses faith in a higher power (well, nobody who isn't an Ewok), or pleads with one for intercession, or draws open strength from theological beliefs. In my opinion, rumors of genuine religion in the Star Wars films are greatly exaggerated. That which doesn't exist can't really be attacked and, conveniently, requires no further defense. As Watto might say, "I need something more real...." So let's get back to ethics.

WHO ARE YOU GOING TO BELIEVE, ME OR THAT OTHER TRILOGY?

The two Star Wars trilogies were filmed nearly two decades apart, and it's fair to say that there is a significant difference in the ethical substance of each set of films. This raises the question of which trilogy should be considered to have, for lack of a better term, precedence in the presumed articulation of the series' ethical vision. The original trilogy, for being the chronological culmination of the sixepisode story? Or the prequel trilogy, for being George Lucas's more recent work, and for the fact that he conceived and directed it from a position of commanding influence, effectively able to do whatever he damn well pleased?

The latter argument might make for intriguing speculation, but for the sake of my argument I'm going to go with the former. After all, we're discussing the ethical content of the films as expressed within their fictional narrative; clearly the chronology of that narrative deserves to win out over the chronology of film production.

With that settled, I can begin to lay out my position that the critical ethical development-the moral articulation which can be considered "victorious" over all others in the Star Wars narrative-is the manner in which Luke Skywalker becomes a Jedi Knight. Lucas has said that the twin trilogies are about the fall and redemption of Darth Vader, but I believe that's only true to a point. Vader is indeed a primary lens through which the events of the films are examined, but if we want to uncover the strongest, most consistent and most admirable thread of virtue in the tapestry, we should pay less attention to the father's journey, and more to the son's.

The Practice Effect

The Practice Effect Infinity's Shore

Infinity's Shore Insistence of Vision

Insistence of Vision Sundiver

Sundiver Brightness Reef

Brightness Reef Existence

Existence The Transparent Society

The Transparent Society Startide Rising

Startide Rising The Postman

The Postman The Uplift War

The Uplift War The Loom of Thessaly

The Loom of Thessaly Otherness

Otherness Sundiver u-1

Sundiver u-1 The Uplift War u-3

The Uplift War u-3 Infinity's Shore u-5

Infinity's Shore u-5 Brightness Reef u-4

Brightness Reef u-4 Uplift 2 - Startide Rising

Uplift 2 - Startide Rising Kiln People

Kiln People Heaven's Reach u-6

Heaven's Reach u-6 The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom?

The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom? Star Wars on Trial

Star Wars on Trial Lungfish

Lungfish Tank Farm Dynamo

Tank Farm Dynamo Just a Hint

Just a Hint A Stage of Memory

A Stage of Memory Foundation’s Triumph sf-3

Foundation’s Triumph sf-3 Thor Meets Captain America

Thor Meets Captain America Senses Three and Six

Senses Three and Six The River of Time

The River of Time Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World

Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World Foundation's Triumph

Foundation's Triumph Startide Rising u-2

Startide Rising u-2 The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf

The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf The Heart of the Comet

The Heart of the Comet The Crystal Spheres

The Crystal Spheres