- Home

- David Brin

Infinity's Shore u-5 Page 2

Infinity's Shore u-5 Read online

Page 2

And then, amid the dazzling rays, he had briefly glimpsed … his captain!

Creideiki …

The blinding glow became a luminous foam, whipped by thrashing flukes. Out of that froth emerged a long gray form whose bottle snout bared glittering teeth. The sleek head grinned, despite bearing an awful wound behind its left eye … much like the hurt that robbed Emerson of speech.

Utterance shapes formed out of scalloped bubbles, in a language like none spoken by Jijo’s natives, or by any great Galactic clan.

In the turning

of the cycloid,

Comes a time

to break for surface.

Time to resume

breathing,

doing.

To rejoin the

great sea’s

dreaming.

Time has come for

you my old friend.

Time to wake and

see what’s churning.… *

Stunned recognition accompanied waves of stinging misery, worse than any fleshy woe or galling numbness.

Shame had nearly overwhelmed him then. For no injury short of death could ever excuse his forgetting—

Creideiki …

Terra …

The dolphins …

Hannes …

Gillian …

How could they have slipped his mind during the months he wandered this barbarian world, by boat, barge, and caravan?

Guilt might have engulfed him during that instant of recollection … except that his new friends urgently needed him to act, to seize the brief advantage offered by the explosion, to overcome their captors and take them prisoner. As dusk fell across the shredded tent and torn bodies, he had helped Sara and Kurt tie up their surviving foes — both urrish and human — although Sara seemed to think their reprieve temporary.

More fanatic reinforcements were expected soon.

Emerson knew what the rebels wanted. They wanted him. It was no secret that he came from the stars. The rebels would trade him to sky hunters, hoping to exchange his battered carcass for guaranteed survival.

As if anything could save Jijo’s castaway races, now that the Five Galaxies had found them.

Huddled round a wan fire, lacking any shelter but tent rags, Sara and the others watched as terrifying portents crossed bitter-cold constellations.

First came a mighty titan of space, growling as it plunged toward nearby mountains, bent on awful vengeance.

Later, following the very same path, there came a second behemoth, this one so enormous that Jijo’s pull seemed to lighten as it passed overhead, filling everyone with deep foreboding.

Not long after that, golden lightning flickered amid the mountain peaks — a bickering of giants. But Emerson did not care who won. He could tell that neither vessel was his ship, the home in space he yearned for … and prayed he would never see again.

With luck, Streaker was far away from this doomed world, bearing in its hold a trove of ancient mysteries — perhaps the key to a new galactic era.

Had not all his sacrifices been aimed at helping her escape?

After the leviathans passed, there remained only stars and a chill wind, blowing through the dry steppe grass, while Emerson went off searching for the caravan’s scattered pack animals. With donkeys, his friends just might yet escape before more fanatics arrived.…

Then came a rumbling noise, jarring the ground beneath his feet. A rhythmic cadence that seemed to go—

taranta taranta

taranta taranta

The galloping racket could only be urrish hoofbeats, the expected rebel reinforcements, come to make them prisoners once again.

Only, miraculously, the darkness instead poured forth allies — unexpected rescuers, both urrish and human — who brought with them astonishing beasts.

Horses.

Saddled horses, clearly as much a surprise to Sara as they were to him. Emerson had thought the creatures were extinct on this world, yet here they were, emerging from the night as if from a dream.

So began the next phase of his odyssey. Riding southward, fleeing the shadow of these vengeful ships, hurrying toward the outline of an uneasy volcano.

Now he wonders within his battered brain — is there a plan? A destination?

Old Kurt apparently has faith in these surprising saviors, but there must be more to it than that.

Emerson is tired of just running away.

He would much rather be running toward.

While his steed bounds ahead, new aches join the background music of his life — raw, chafed thighs and a bruised spine that jars with each pounding hoofbeat.

taranta, taranta, taranta-tara

taranta, taranta, taranta-tara

Guilt nags him with a sense of duties unfulfilled, and he grieves over the likely fate of his new friends on Jijo, now that their hidden colony has been discovered.

And yet …

In time Emerson recalls how to ease along with the sway of the saddle. And as sunrise lifts dew off fan-fringed trees near a riverbank, swarms of bright bugs whir through the slanted light, dancing as they pollinate a field of purple blooms. When Sara glances back from her own steed, sharing a rare smile, his pangs seem to matter less. Even fear of those terrible starships, splitting the sky with their angry engine arrogance, cannot erase a growing elation as the fugitive band gallops on to dangers yet unknown.

Emerson cannot help himself. It is his nature to seize any possible excuse for hope. As the horses pound Jijo’s ancient turf, their cadence draws him down a thread of familiarity, recalling rhythmic music quite apart from the persistent dirge of woe.

tarantara, tarantara

tarantara, tarantara

Under insistent stroking by that throbbing sound, something abruptly clicks inside. His body reacts involuntarily as unexpected words surge from some dammed-up corner of his brain, attended by a melody that stirs the heart. Lyrics pour reflexively, an undivided stream, through lungs and throat before he even knows that he is singing.

“Though in body and in mind, {tarantara, tarantara}

We are timidly inclined, {tarantara!}

And anything but blind, {tarantara, tarantara}

To the danger that’s behind— {tarantara!}

His friends grin — this has happened before.

“Yet, when the danger’s near, {tarantara, tarantara}

We manage to appear, {tarantara!}

As insensible to fear,

As anybody here,

As an-y-bo-dy here!”

Sara laughs, joining the refrain, and even the dour urrish escorts stretch their long necks to lisp along.

“Yet, when the danger’s near, {tarantara, tarantara}

We manage to appear, {tarantara!}”

As insensible to fear,

As anybody here,

As anybody here!”

PART ONE

EACH OF THE SOONER RACES making up the Commons of Jijo tells its own unique story, passed down from generation to generation, explaining why their ancestors surrendered godlike powers and risked terrible penalties to reach this far place — skulking in sneakships past Institute patrols, robot guardians, and Zang globules. Seven waves of sinners, each coming to plant their outlaw seed on a world that had been declared off-limits to settlement. A world set aside to rest and recover in peace, but for the likes of us.

THE g’Kek arrived first on this land we call the Slope, between misty mountains and the sacred sea — half a million years after the last legal tenants — the Buyur — departed Jijo.

Why did those g’Kek founders willingly give up their former lives as star-traveling gods and citizens of the Five Galaxies? Why choose instead to dwell as fallen primitives, lacking the comforts of technology, or any moral solace but for a few engraved platinum scrolls?

Legend has it that our g’Kek cousins fled threatened extinction, a dire punishment for devastating gambling losses. But we cannot be sure. Writing was a lost art until humans came, so th

ose accounts may be warped by passing time.

What we do know is that it could not have been a petty threat that drove them to abandon the spacefaring life they loved, seeking refuge on heavy Jijo, where their wheels have such a hard time on the rocky ground. With four keen eyes, peering in all directions at the end of graceful stalks, did the g’Kek ancestors see a dark destiny painted on galactic winds? Did that first generation see no other choice? Perhaps they only cursed their descendants to this savage life as a last resort.

NOT long after the g’Kek, roughly two thousand years ago, a party of traeki dropped hurriedly from the sky, as if fearing pursuit by some dreaded foe. Wasting no time, they sank their sneakship in the deepest hollow of the sea, then settled down to be our gentlest tribe.

What nemesis drove them from the spiral lanes?

Any native Jijoan glancing at those familiar stacks of fatty toruses, venting fragrant steam and placid wisdom in each village of the Slope, must find it hard to imagine the traeki having enemies.

In time, they confided their story. The foe they fled was not some other race, nor was there a deadly vendetta among the star gods of the Five Galaxies. Rather, it was an aspect of their own selves. Certain rings — components of their physical bodies — had lately been modified in ways that turned their kind into formidable beings. Into Jophur, mighty and feared among the noble Galactic clans.

It was a fate those traeki founders deemed unbearable. So they chose to become lawless refugees — sooners on a taboo world — in order to shun a horrid destiny.

The obligation to be great.

• • •

IT is said that glavers came to Jijo not out of fear, but seeking the Path of Redemption — the kind of innocent oblivion that wipes all slates clean. In this goal they have succeeded far better than anyone else, showing the rest of us the way, if we dare follow their example.

Whether or not that sacred track will also be ours, we must respect their accomplishment — transforming themselves from cursed fugitives into a race of blessed simpletons. As starfaring immortals, they could be held accountable for their crimes, including the felony of invading Jijo. But now they have reached a refuge, the purity of ignorance, free to start again.

Indulgently, we let glavers root through our kitchen middens, poking under logs for insects. Once mighty intellects, they are not counted among the sooner races of Jijo anymore. They are no longer stained with the sins of their forebears.

QHEUENS were the first to arrive filled with wary ambition.

Led by fanatical, crablike gray matrons, their first-generation colonists snapped all five pincers derisively at any thought of union with Jijo’s other exile races. Instead, they sought dominion.

That plan collapsed in time, when blue and red qheuens abandoned historic roles of servitude, drifting off to seek their own ways, leaving their frustrated gray empresses helpless to enforce old feudal loyalties.

OUR tall hoonish brethren inhale deeply, whenever the question arises—“Why are you here?” They fill their prodigious throat sacs with low meditation umbles. In rolling tones, hoon elders relate that their ancestors fled no great danger, no oppression or unwanted obligations.

Then why did they come, risking frightful punishment if their descendants are ever caught living illegally on Jijo?

The oldest hoons on Jijo merely shrug with frustrating cheerfulness, as if they do not know the reason, and could not be bothered to care.

Some do refer to a legend, though. According to that slim tale, a Galactic oracle once offered a starfaring hoonish clan a unique opportunity, if they dared take it. An opportunity to claim something that had been robbed from them, although they, never knew it was lost. A precious birthright that might be discovered on a forbidden world.

But for the most part, whenever one of the tall ones puffs his throat sac to sing about past times, he rumbles a deep, joyful ballad about the crude rafts, boats, and seagoing ships that hoons invented from scratch, soon after landing on Jijo. Things their humorless star cousins would never have bothered looking up in the all-knowing Galactic Library, let alone have deigned to build.

LEGENDS told by the fleet-footed urrish clan imply that their foremothers were rogues, coming to Jijo in order to breed—escaping limits imposed in civilized parts of the Five Galaxies. With their short lives, hot tempers, and prolific sexual style, the urs founders might have gone on to fill Jijo with their kind … or else met extinction by now, like the mythical centaurs they vaguely resemble.

But they escaped both of those traps. Instead, after many hard struggles, at the forge and on the battlefield, they assumed an honored place in the Commons of Six Races. With their thundering herds, and mastery of steel, they live hot and hard, making up for their brief seasons in our midst.

FINALLY, two centuries ago, Earthlings came, bringing chimpanzees and other treasures. But humans’ greatest gift was paper. In creating the printed trove of Biblos, they became lore masters to our piteous commonwealth of exiles. Printing and education changed life on the Slope, spurring a new tradition of scholarship, so that later generations of castaways dared to study their adopted world, their hybrid civilization, and even their own selves.

As for why humans came all this way — breaking Galactic laws and risking everything, just to huddle with other outlaws under a fearsome sky — their tale is among the strangest told by Jijo’s exile clans.

from An Ethnography of the Slope,

by Dorti Chang-Jones and Huph-alch-Huo

Sooners

Alvin

I HAD NO WAY TO MARK THE PASSAGE OF TIME, LYING dazed and half-paralyzed in a metal cell, listening to the engine hum of a mechanical sea dragon that was hauling me and my friends to parts unknown.

I guess a couple of days must have passed since the shattering of our makeshift submarine, our beautiful Wuphon’s Dream, before I roused enough to wonder, What next?

Dimly, I recall the sea monster’s face as we first saw it through our crude glass viewing port, lit by the Dream’s homemade searchlight. That glimpse lasted but a moment as the huge metal thing loomed toward us out of black, icy depths. The four of us — Huck, Pincer, Ur-ronn, and me — had already resigned ourselves to death … doomed to crushed oblivion at the bottom of the sea. Our expedition a failure, we didn’t feel like daring subsea adventurers anymore, but like scared kids, voiding our bowels in terror as we waited for the cruel abyss to squeeze our hollowed-out tree trunk into a zillion soggy splinters.

Suddenly this enormous shape erupted toward us, spreading jaws wide enough to snatch Wuphon’s Dream whole.

Well, almost whole. Passing through that maw, we struck a glancing blow.

The collision shattered our tiny capsule.

What followed still remains a painful blur.

I guess anything beats death, but there have been moments since that impact when my back hurt so much that I just wanted to rumble one last umble through my battered throat sac and say farewell to young Alvin Hph-wayuo — junior linguist, humicking writer, uttergloss daredevil, and neglectful son of Mu-phauwq and Yowg-wayuo of Wuphon Port, the Slope, Jijo, Galaxy Four, the Universe.

But I stayed alive.

I guess it just didn’t seem hoonish to give up, after everything my pals and I went through to get here. What if I was sole survivor? I owed it to Huck and the others to carry on.

My cell — a prison? hospital room? — measures just two meters, by two, by three. Pretty skimpy for a hoon, even one not quite fully grown. It gets even more cramped whenever some six-legged, metal-sheathed demon tries to squeeze inside to tend my injured spine, poking with what I assume (hope!) to be clumsy kindness. Despite their efforts, misery comes in awful waves, making me wish desperately for the pain remedies cooked up by Old Stinky — our traeki pharmacist back home.

It occurred to me that I might never walk again … or see my family, or watch seabirds swoop over the dross ships, anchored beneath Wuphon’s domelike shelter trees.

I tried talki

ng to the insecty giants trooping in and out of my cell. Though each had a torso longer than my dad is tall — with a flared back end, and a tubelike shell as hard as Buyur steel — I couldn’t help picturing them as enormous phuvnthus, those six-legged vermin that gnaw the walls of wooden houses, giving off a sweet-tangy stench.

These things smell like overworked machinery. Despite my efforts in a dozen Earthling and Galactic languages, they seemed even less talkative than the phuvnthus Huck and I used to catch when we were little, and train to perform in a miniature circus.

I missed Huck during that dark time. I missed her quick g’Kek mind and sarcastic wit. I even missed the way she’d snag my leg fur in her wheels to get my attention, if I stared too long at the horizon in a hoonish sailor’s trance. I last glimpsed those wheels spinning uselessly in the sea dragon’s mouth, just after those giant jaws smashed our precious Dream and we spilled across the slivers of our amateur diving craft.

Why didn’t I rush to my friend, during those bleak moments after we crashed? Much as I yearned to, it was hard to see or hear much while a screaming wind shoved its way into the chamber, pushing out the bitter sea. At first, I had to fight just to breathe again. Then, when I tried to move, my back would not respond.

In those blurry instants, I also recall catching sight of Ur-ronn, whipping her long neck about and screaming as she thrashed all four legs and both slim arms, horrified at being drenched in vile water. Ur-ronn bled where her suede-colored hide was pierced by jagged shards — remnants of the glass porthole she had proudly forged in the volcano workshops of Uriel the Smith.

Pincer-Tip was there, too, best equipped among our gang to survive underwater. As a red qheuen, Pincer was used to scampering on five chitin-armored claws across salty shallows — though our chance tumble into the bottomless void was more than even he had bargained for. In dim recollection, I think Pincer seemed alive … or does wishful thinking deceive me?

The Practice Effect

The Practice Effect Infinity's Shore

Infinity's Shore Insistence of Vision

Insistence of Vision Sundiver

Sundiver Brightness Reef

Brightness Reef Existence

Existence The Transparent Society

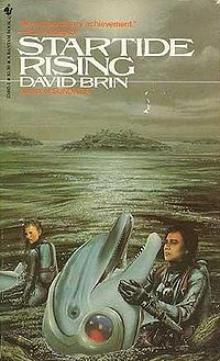

The Transparent Society Startide Rising

Startide Rising The Postman

The Postman The Uplift War

The Uplift War The Loom of Thessaly

The Loom of Thessaly Otherness

Otherness Sundiver u-1

Sundiver u-1 The Uplift War u-3

The Uplift War u-3 Infinity's Shore u-5

Infinity's Shore u-5 Brightness Reef u-4

Brightness Reef u-4 Uplift 2 - Startide Rising

Uplift 2 - Startide Rising Kiln People

Kiln People Heaven's Reach u-6

Heaven's Reach u-6 The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom?

The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom? Star Wars on Trial

Star Wars on Trial Lungfish

Lungfish Tank Farm Dynamo

Tank Farm Dynamo Just a Hint

Just a Hint A Stage of Memory

A Stage of Memory Foundation’s Triumph sf-3

Foundation’s Triumph sf-3 Thor Meets Captain America

Thor Meets Captain America Senses Three and Six

Senses Three and Six The River of Time

The River of Time Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World

Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World Foundation's Triumph

Foundation's Triumph Startide Rising u-2

Startide Rising u-2 The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf

The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf The Heart of the Comet

The Heart of the Comet The Crystal Spheres

The Crystal Spheres