- Home

- David Brin

Star Wars on Trial Page 4

Star Wars on Trial Read online

Page 4

In twenty-two episodes, the younger Jones, played by Sean Patrick Flanery, encountered one after another of the greatest minds of the early part of the twentieth century, learning from them, not only as Campbellian journey mentors or spirit guides, but as archetypes of adult ambition and achievement, nearly always representing some key ingredient in a rambunctiously eager and hopeful civilizationfrom jazz musicians to saintly jungle doctors, from inventors to master spies, from mothers to fathers. And, yes, in confronting war and oppression, firsthand, Indy (and the viewers) learned about civilization's "dark side." There were dour reflections, amid all the dashing, heroic deeds. Though throughout, young Indy never lost faith in the power of reason, discovery and science.

Picture Huckleberry Finn on a raft escapade with Ben Franklin. Imagine something written for all ages, all the parts of your brain.

Alas, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles sometimes got too lecturey and lost pace. Its relative commercial failure provokes one to wonder: did George Lucas learn a lesson-the wrong lesson-never again to even try blending the adult and the child, offering something to both?

No, there are plenty of counterexamples, some even provided by George Lucas, to the dismal notion that we must enslave ourselves to a single, tedious storytelling pattern, even if it pervaded many cultures of the past. Especially because it pervaded so many failed, oppressive societies of our bloody, awful past.

Which is why science fiction-the real thing-came as such a radical departure. A new kind of storytelling, it often rebels against the very archetypes that Aristotle and the Campbellians venerate.

Take the occasional upstart belief that progress, egalitarianism and positive-sum games are possible-if very hard. Or hopeful confidence in a slim, but very real, possibility of decent human institutions.

Then there is the upstart habit of compulsively questioning rules! Even rules of storytelling. Authors like John Brunner, Alice Sheldon, Cordwainer Smith, Greg Bear, Frederik Pohl and Philip K. Dick always looked on any prescriptive storytelling formula as a direct challenge-a dare. A reason to try something different, for a change.

This explains why science fiction has never been much welcomed at either extreme of the literary spectrum-either in comic books or in the halls of "high literature."

BOTH ENDS AGAINST THE MIDDLE

You'd think that science fiction would be natural for comics. Some of our best living graphic artists have become adept, using this static, two-dimensional medium, at conveying startlingly vivid and evocative effects in sequential panels-the kind of imagery that caters naturally to futuristic or exotic locales. And there are other overlaps between SF and comics. For example, both genres are unafraid to posit the possibility of garish transformation and change.

Nevertheless, for decades, people have wondered why illustrated graphic novels and comics focus so thoroughly on superheroes, hardly ever telling the kinds of vivid space or future-oriented adventures penned by Verne, Wells, Vinge, de Camp, Anderson, Pohl, Heinlein and so on.

Returning to the ongoing theme of this essay, you can find a possible explanation in how the writers and publishers of these marvelous illustrated tales treat their superheroes-with reverent awe, as demigods were depicted in The Iliad. All of the complaints listed earlier about minimizing the importance of normal people-of civilization-apply as much to comics as they do to Star Wars. Comics appear to have their roots firmly planted in the old archetypes. Far too firmly ever to welcome the spirit of true sci-fi.

Or, at least, that is how comics treated their heroes ... until recently. Changes do appear to be afoot at last, however. In one of the great ironies, while literary SF has been turning ever more toward the styles and sensibilities of fantasy, many of the best comic book and graphic novel writers have lately been writing almost as if they were ... well ... science fiction authors!

What's the crucial distinction?

Imagine, for a moment, how a true science fiction author might write about Superman. Picture earthling scientists asking the handsome Man of Steel for blood samples (even if it means scraping with a super fingernail) in order to study his puissant powers. And then ... maybe ... bottling the trick for everyone?

As for the opposite end of the spectrum-the literary elite-it's easy to see that campus postmodernists despise science fiction in part because of the word "science." Another reason is that many scholars find anathema the underlying assumption behind most high-quality SF: a bold assertion that there are no "eternal human verities." Things change. Change can be fascinating. And science fiction is the literature of change.

Moreover, our children might outgrow us! They may become better, or learn from our mistakes and not repeat them. And if they don't learn? That could be a riveting tragedy, far exceeding Aristotle's cramped, myopic definition.

On the Beach, Soylent Green and 1984 plumbed frightening depths. Brave New World, "The Screwfly Solution" and Fahrenheit 451 posed worrying questions. In contrast, Oedipus Rex is about as interesting as watching a hooked fish thrash futilely at the end of a line. A modern person may weep at the right moments, as the playwright intended. Only then, you just want to put the poor doomed King of Thebes out of his misery-and find a way to punish his tormentors.

This truly is a different point of view, in direct opposition to older, elitist creeds that preached passivity and awe in nearly every culture. Where asking too many questions was punishable hubris. Where a hero's job was to oppose one set-piece villain ... in order to defend the aristocratic rights of another.

Imagine Achilles refusing to accept his ordained destiny, taking up his sword and hunting down the Fates, demanding that they give him both a long life and a glorious one! Picture Odysseus telling both Agamemnon and Poseidon to go chase themselves, then heading off to join Dae dalus in a garage start-up company, mass-producing both wheeled and winged horses, so mortals could swoop about the land and air, like gods-the way common folk do nowadays, so unaware what they are part of. A marvel of collaborative technological progress.

Even if their start-up fails and jealous Olympians crush Odysseus/ DaedalusCorp, what a tale it would be!

Can this attitude work in stories? Consider those lowbrow but way fun television series Hercules, Buffy and Xena. Though they wore all the trappings of fantasy-swords and magical spells-each episode told a morality tale that was fiercely pro-democracy, egalitarian, hubristic and rambunctiously antiaristocratic. (In contrast, Star Wars, for all of its laser furniture, appears to defend every mythological aspect of feudalism.)

This new storytelling style was rarely seen till a few generations ago, when aristocrats lost some of their power to punish irreverence. And even now, the new perspective remains shaky. The older notion of punishable "hubris" still pervades a wide range of literature and film, from highbrow to low. From the works of Michael Crichton to those of Margaret Atwood, how many dramas reflexively depict scientists as "mad"? How few depict change in a positive light, or show public institutions functioning well enough to bother fixing them?

No wonder George Lucas openly yearns for the pomp of mighty kings over the drab accountability of republics. Many share his belief that things might be a whole lot more vivid without all the endless, dreary argument and negotiating that make up such a large part of modern life. Even millions of voters have taken to supporting authoritarians, who seek power free of accountability. Aristocrats who say "trust me."

The old yearning is still strong.

For someone to take command. A leader.

THE SHIFTY NOTION OF REBELLION

Ah, but the Star Wars series didn't begin obsessed with leaders. It started as a story about rebels, bravely taking on an empire!

I cannot repeat enough times that I had no particular trouble with the original Star Wars movie-since relabeled A New Hope. Lightweight and a bit silly, it nevertheless oozed charm, adventure and good-hearted egalitarian fun. The villain, with a name like "invader," wore a Nazi-style helmet, commanded "stormtroopers" and torture-interrogated pr

incesses. He throttled brave rebel captains with his bare hands and helped blow up planets. Clearly this film played into the greatest American mythos-in fact, the most stunning propaganda campaign of all time-

-suspicion of authority.

No, your eyes do not deceive you. Just pause and think about it.

Arguably, the most persistent and incessant propaganda campaign, appearing in countless American movies, novels, myths and TV shows, preaches a message quite opposite to the one we associate with Joseph Campbell. A singular and unswerving theme, so persistent and ubiquitous that most people hardly notice or mention it. And yet, I defy you to name even half a dozen popular movies that don't utilize its appeal.

Yes, that theme is suspicion of authority-often accompanied by its junior sidekick tolerance. Indeed, watch the heroes of nearly every modern film. Don't most of them bond with the viewer by sticking it to some authority figure, often in the first few minutes?

Oh, you do hear some messages of conformity and intolerance, but these fill the mouths of moustache-twirling villains, clearly inviting us to rebel contrary to everything they say. Submission to gray tribal normality is portrayed as one of the most contemptible things an individual can do-a message quite opposite to what was pushed in most other cultures.' Take the wildly popular movie E. T. whose central message goes something like this: "Little American children, if you ever meet a strange alien from beyond the pale, by all means hide him from your own freely elected tribal elders!" I reiterate, no other society preached such a lesson to its offspring.

Now let me admit, where this strange suspicion-of-authority propaganda campaign comes from I don't know. Even after talking about it publicly for years, I don't have a good theory! Yet, its effects are inarguably spectacular, underlying most of the accomplishments of modern-enlightenment civilization. Half of our prodigious creativity may arise from a restless need to be different in order to prove a sense of individuality that we absorbed from an early age.

Alas, it also results in an occasional Timothy McVeigh ... the kind of malignant obsessive who never gets the overarching irony-that his own proud antiauthoritarianism was suckled at an early age from the very society he despised, spoon-fed to him and millions of other youths by a civilization that does everything possible to create wave after wave of rambunctious rebels.

Rebels. No wonder A New Hope (ANH) had such resonance. The Empire's bad, so fight it!

Moreover, nostalgia for the Old Republic wasn't yet tainted with the utter contempt for democracy that would pervade Episodes I-III.

Indeed, this rebel spirit continued in The Empire Strikes Back (TESB). Even though we met Yoda-an authority figure to whom our hero had to bow-neither the Jedi Master nor the Force were yet the cloying, oppressive things they would later become. According to critic Stefan Jones, "In the first film, the Force was a kind of martial art/Zen archery kind of thing. Rather egalitarian: Obi-Wan even offers to teach scoffer Han Solo the ropes, implying anybody can do it. Goofy comic-book mysticism, but kind of charming and innocent, in a Hong Kong kung-fu movie sort of way." And even though Yoda starts throwing his diminutive weight around, in TESB, the lessons are still pretty benign.

Stay calm and focused. Um, sure, sounds good. My kids learn the same thing, at their karate studio.

Anyway, Luke even rebels against that authority figure! Yoda warns: "If you go and help your friends, lost everything will be!"

But Luke goes anyway... and lost everything is not! (Whereupon, faced with awkward questions, Yoda performs a handy escape trick. The old "death" fadeaway!)

Alas, as the Ubermensch Effect took over-starting in Return of the Jedi (ROTJ) and worsening with every film that followed-the Force grew ever more elitist. You had to be born with it! No, not just born with it, you had to be a mutant. No, make that a fore-ordained by destiny, preselected long ago, out-and-out messiah. A bona fide Chosen One. A demigod.

In a progressive universe, Yoda and his competitor sages would set up Jedi-arts studios in every mini-mall on Coruscant-the way karate saturates suburban America-giving millions of kids exposure to a little discipline and fun, plus a chance to better themselves through hard work. Maybe outperform what cynical grown-ups expect of them. But Yoda thinks he can diagnose at age nine who's got it, who hasn't. And who is destined to fail before they try.

Only demigods need apply... and only those demigods Yoda likes.

But more about the nasty green oven mitt anon.

MORE COMPARISONS

Again, is all of this serious rumination just spoilsport grumbling? Or worse, sour grapes? Why look for deep lessons in harmless, escapist entertainment? While some earnestly hold that the moral health of a civilization can be traced in its popular culture, don't moderns tend to feel that ideas, even unpleasant ones, aren't inherently toxic in their own right?

And yet who can deny that people-especially children-will be swayed if a message is repeated often enough? It's when a "lesson" gets reiterated relentlessly that even skeptics should sit up and take notice.

Don't be fooled. The moral messages in Star Wars aren't just window dressing. Speeches and lectures drench every film. They take up the slack time that could have been spent on plotting.

They represent an agenda.

Let's go back to comparing George Lucas's space-adventure epic to its chief competitor-Star Trek. The differences at first seem superficial, but they add up.

We have already see how one saga has an air force motif (tiny fighters) while the other appears naval. In Star Trek, the big ship is heroic and the cooperative effort required to maintain it is depicted as honorable. Indeed, Star Trek sees technology as useful and es sentially friendly-if at times also dangerous. Education is a great emancipator of the humble (e.g., Starfleet Academy). Futuristic institutions are basically good-natured (the Federation), though of course one must fight outbreaks of incompetence, secrecy and corruption. Professionalism is respected, lesser characters make a difference, and henchmen often become brave whistle-blowers-as they do in America today.

In Star Trek, when authorities are defied, it is in order to overcome their mistakes or expose particular villains, not to portray all government as inherently hopeless. Good cops sometimes come when you call for help. Ironically, this image fosters useful criticism of authority, because it suggests that any of us can gain access to our flawed institutions-if we are determined enough-and perhaps even fix them with fierce tools of citizenship.

Above all, whenever you encounter Homo superior in Star Treksome hyper-evolved, better-than-human fellow with powers beyond our mortal kin-the demigod is subjected to scrutiny and skeptical worry! Such mutant uber-types are given a chance to prove they mean no harm. But when they throw their weight around, normal folk rise up and look them in the eye. This happens so often in Trek-as well as shows like Stargate and Babylon 5-that it has become a true sci-fi tradition.

By contrast, the choices in Star Wars are stark and limited. As in Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, you can join either the Dark Lord or the Chosen Prince (with his pointy-eared elf advisors). Ultimately, the oppressed "rebels" in Star Wars have no recourse in law or markets or science or democracy. They can only pick sides in a civil war between two wings of the same genetically superior royal family.

(The same royal family? Oh, but it's right there, in front of you! The implication that bubbles out of the quirky SW obsession, with heaping coincidence upon coincidence. The Emperor comes from the same narrow aristocracy-on Planet Naboo-as Luke's mother. Probably, they're cousins. As for Anakin's mother, who's to say she didn't come from the same place? A gene pool of midichlorian mutants, engaged in a family spat, and galaxy-wide hell ensues. It's a reach, but thoughtprovoking. Is it any wonder that, in Star Trek, demigod mutants are always treated with skepticism, not reflex worship?)

Yes, Star Trek had its own problems and faults. The television episodes often devolved into soap operas. Many of the movies were very badly written. Trek at times seemed preachy, or turgidly politically

correct, especially in its post-Kirk incarnations. (For example, every species has to mate with every other one, interbreeding with almost compulsive abandon. The only male heroes who are allowed any testosterone-in The Next Generation-are Klingons, because cultural diversity outweighs sexual correctness. In other words, it's okay for them to be macho 'cause it is "their way.") Nevertheless, Trek tried to grapple with genuine issues, giving complex voices even to its villains and asking hard questions about pitfalls we may face while groping for tomorrow.

Anyway, when it comes to portraying human destiny, where would you rather live, assuming you'll be a normal citizen and no demigod? In Roddenberry's Federation? Or Lucas's Empire?

THE FEUDAL REFLEX

George Lucas defends his elitist view, telling the New York Times, "That's sort of why I say a benevolent despot is the ideal ruler. He can actually get things done. The idea that power corrupts is very true and it's a big human who can get past that."3 He further says we are a sad culture, bereft of the confidence or inspiration that strong leaders can provide.

And yet, aren't we the very same culture that produced George Lucas and gave him so many opportunities? The same society that raised all those brilliant experts for him to hire-boldly creative folks who pour both individual inspiration and cooperative skill into his films, working at a monolithic corporate institution that nevertheless, functions pretty well?

A culture that defies the old homogenizing impulse by worshipping eccentricity, with unprecedented hunger for the different, new or strange? In what way can such a civilization be said to lack confidence? And just how would a king or despot help?

In historical fact, all of history's despots, combined, never managed to "get things done" as well as this rambunctious, self-critical civilization of free and sovereign citizens, who have finally broken free of worshipping a ruling class and begun thinking for themselves. Democracy can seem frustrating and messy at times, but it delivers. So why do few filmmakers-other than Steven Spielberg-own up to that basic fact?

The Practice Effect

The Practice Effect Infinity's Shore

Infinity's Shore Insistence of Vision

Insistence of Vision Sundiver

Sundiver Brightness Reef

Brightness Reef Existence

Existence The Transparent Society

The Transparent Society Startide Rising

Startide Rising The Postman

The Postman The Uplift War

The Uplift War The Loom of Thessaly

The Loom of Thessaly Otherness

Otherness Sundiver u-1

Sundiver u-1 The Uplift War u-3

The Uplift War u-3 Infinity's Shore u-5

Infinity's Shore u-5 Brightness Reef u-4

Brightness Reef u-4 Uplift 2 - Startide Rising

Uplift 2 - Startide Rising Kiln People

Kiln People Heaven's Reach u-6

Heaven's Reach u-6 The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom?

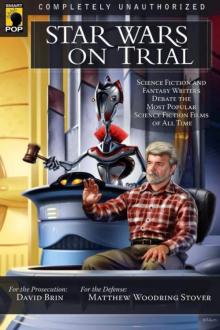

The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force Us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom? Star Wars on Trial

Star Wars on Trial Lungfish

Lungfish Tank Farm Dynamo

Tank Farm Dynamo Just a Hint

Just a Hint A Stage of Memory

A Stage of Memory Foundation’s Triumph sf-3

Foundation’s Triumph sf-3 Thor Meets Captain America

Thor Meets Captain America Senses Three and Six

Senses Three and Six The River of Time

The River of Time Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World

Chasing Shadows: Visions of Our Coming Transparent World Foundation's Triumph

Foundation's Triumph Startide Rising u-2

Startide Rising u-2 The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf

The Fourth Vocation of George Gustaf The Heart of the Comet

The Heart of the Comet The Crystal Spheres

The Crystal Spheres